Dissertation Topic: An investigation into the experience of writing academic essays in English of postgraduate Chinese overseas students

Abstract

This study on Nature of Academic Writing investigated how the two established models of English writing – the product approach and the process approach – affected Chinese MA TESOL postgraduate students’ essay writing, data resources including questionnaires and self-report with stimulated recall protocols in the interviews. The types of writing activities that students went through in the journey of writing an academic essay were taken into account when exploring features of writing processes in the reader-focused approach.

This research used a questionnaire and interviews. 60 Chinese postgraduate students for MA TESOL in a university in UK took part in the questionnaire survey. Participants were recruited by sharing website link for the questionnaires via Chinese TESOL group chat, for example, Wechat (a Chinese version Facebook). The semi-structured interview was carried out with 10 Chinese postgraduate students among the participants of the questionnaire who were chosen by convenience sampling.

Findings from the questionnaire showed that all the participants highlighted the significance of writing activities of the process-oriented approach to their writing experiences in terms of academic essay writing. Interviewees explained the reasons why Chinese international students preferred to adopt process-oriented writing activities in the experiences of academic essay writing and they evaluated the benefits and challenges of both writing approaches — the product approach and the process approach — to emphasise the positive effect of the process approach on the essay composition.

The implication of these findings for nature of academic writing was that Chinese overseas students gained benefits from both the product approach and the process approach. For example, model samples, which appeared at the first stage of the product approach, offered students a broad exposure to the language structure related to the writing topics, while these texts were used as a feedback technique in the stage of revising in the process approach.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 The nature of academic writing

A large number of studies (Bailey, 2015; Friedrich, 2008) have shown that many academic courses in postgraduate programmes test students through written assignments. These studies have revealed the significance of essays or dissertations in higher educational study. Written tasks, including project reports and commentaries, normally take more than a week to write, and written examinations that need to be handed in once students finished, normally last for about 2 hours (Bailey, 2015). It is challenging for students to complete a writing task with higher quality in such a tense period of time to understand nature of academic writing.

Input knowledge required in English writing varies according to different text types (Nation, 2008). Bailey (2015) and Nation (2008) state that one of the most important essences of academic writing for students is to value the depth of subject knowledge that lecturers expect students to acquire, and it is also one of means to communicate through written form for other readers and scholars in academic fields (Paltridge, Harbon, Hirsh, Shen, Stevenson, Phakiti & Woodrow, 2009). Successful academic writing, sometimes, also needs students to cooperate with members in groups via a series of practice in reading, writing, evaluating, arguing, and editing (Nation, 2008). Research shows (e.g. Yang, 2016) that Chinese postgraduates often have difficulty in meeting the requirements of academic essays and do not know what should be included. The content of assignments such as project report, commentary and final essay is unclear for those students who have never written these before.

Different academic departments have different expectations in essay writing, which to some extent, cause confusion when students have several essays to complete and obey many disciplines at the same time (Nation, 2008; Paltridge et al., 2009). For example, the requirements of references as the last part of a thesis or dissertation could be distinct among different majors. Some teachers demand that references are the texts that students have quoted in the in-text citation while other lecturers refer reference as bibliography that is helpful to construct students’ written assignments, systemize their structure and even change their thoughts in preparing their essays.

In ESL/EFL educational settings, many approaches to teach English writing have been proposed. Knowing the dissimilarities among these approaches can facilitate the progress of essay writing because of students’ critical evaluation on the benefits and challenges of various writing approaches (Badger & White, 2000). The product approach and the process approach are two of the most essential writing approaches in the course of English writing development, after which other writing approaches such as genre-focused approach and process genre approach create. The terms of the product approach and the process approach were elaborated clearly in the following literature review.

1.2 Research Questions (Nature of academic writing)

- In what ways do Chinese PG students describe how they have been taught to write essays during their schooling?

- How do Chinese PG students characterise their experiences of essay writing now as overseas students?

- Which methods do Chinese PG students use in their essay writing in English?

- What do they perceive to be the challenges and benefits of these processes?

1.3 Dissertation Structure (Nature of academic writing)

This dissertation is divided into six chapters. Chapter one begins with a brief introduction of the whole paper, consisting of the nature of academic writing, research questions as well as the structure of the paper. Chapter two, the literature review, provides the concept of two established models, which contains reviews of previous research on the product approach, the process approach and an explanation on the writing stages of the process approach. Chapter three gives a detailed research methodology used in this study, which states the research questions, participants, the data collection instruments, procedures, pilot study and ethical considerations. Chapter four presents the analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from the questionnaires and semi-structured interviews following the sequence of four research questions. Chapter five reveals the link between the findings of the present study and the findings of previous research, which is followed by Chapter six, a conclusion of the main findings and limitations of this study, as well as suggestions for future research.

Chapter 2: Literature Review (Nature of academic writing)

This chapter presents a review of literature relevant to two dominant writing approaches – product approach and process approach, and issues of applying the two approaches in the Chinese context. It consists of four main sections. The first section offers an explanation of the two dominant approaches that second language (L2) teachers use in L2 classroom and writing stages for the two approaches. The second section mainly analyses writing stages of the process approach which will be fully discusses in the following content and it is the main approach that will be investigated in the present questionnaire and interviews. The third section lists the previous studies of both the product and process approach on the condition of ESL/EFL settings. The final section introduces research samples using for this questionnaire design.

2.1 The product approach

The product approach, theoretically based on behaviourism, can be seen as the most popular teaching strategy in Chinese ESL/EFL settings especially for English beginners (Zhang, 2012). Behaviourism, a learning theory, emphasizes on the stimulus from outside environment where observable behaviours happen (Skinner, 1985). That is to say, the ability to acquire relative knowledge will be strengthened on the condition of repetitive learning activities. Based on this behaviourist theory, pedagogical process of teaching English writing relies the most on students’ reaction to teachers’ stimulus, in which teachers at first provide a clear, accurate and concrete model sample for students, explain and analyse a model sample, then students are required to give a response (e.g. write on the given form) to reinforce the writing ability and finally teachers will evaluate the finished text and give feedback (Dovey, 2010). This teaching pattern is teacher-focused making the whole writing class under teacher’s control.

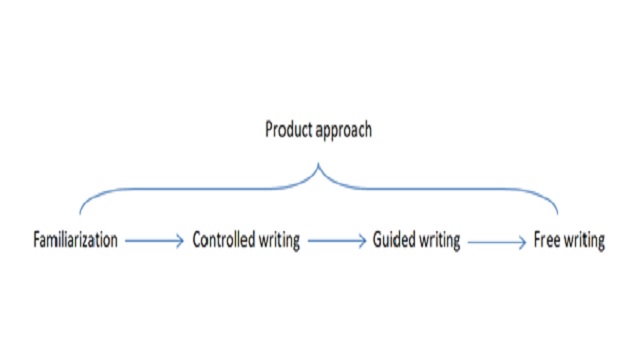

The product approach, where writing process has been described as a linear experience, generally comprises of four stages (see Picture 1): “familiarization; controlled writing; guided writing; and free writing” (Badger & White, 2000, p.153).

(Picture 1)

The purpose of familiarization is to make students aware of typical features of each text type (Badger & White, 2000; Khuder & Harwood, 2015). The experiences of writing various types of texts, such as an invitation and academic essay are different. Writers use convincing language like can help instead of may help in an academic essay in order to support their statement firmly and convince others, while an invitation letter is more emotional as the invitation is expected to be accepted (Friedrich, 2008; Paltridge et al., 2009). In the second writing stage, named controlled, students are asked to write a composition by imitating a fixed model, the feature of which is to strictly follow the disciplines of social context (Badger & White, 2000). Students need to practice a formal content organization, and language should be more academic when they create a research report or an academic essay. Hasan and Akhand (2010) state that the section of guided writing is the most important stage in which the ideas are organised, especially for those people who believe that the organizational structure is the soul of an excellent written material. It is in the habit formation that well-structured content helps readers to understand more easily by organizing supporting ideas and arguments in a clear and conventional order (Bailey, 2015; Zhu, 2004). The final section, called free writing, usually is the end of product writing approach where English learners write the composition independently by using the vocabularies, grammars, structures and writing skills that have been practised (Badger & White, 2000). This offers learners enough freedom and increases their confidence once they complete the product.

In conclusion, the main features of the product approach were summarized as follow: The product approach emphasizes the importance of stimulus and imitation of the learning experience and needs more practice; It relies on the language of model texts; Students normally focus on the final product rather than enjoying the experience of writing; Teachers respond to students’ draft in the final stage and students seldom rewrite their composition after receiving the feedback. The product approach has a positive influence in enhancing students’ writing skills and proficiency (Badger & White, 2000), however, the process approach has been defined as a more scientific and systematic pedagogy in teaching ESL/EFL writing (Nordin & Mohammad, 2017).

2.2The process approach

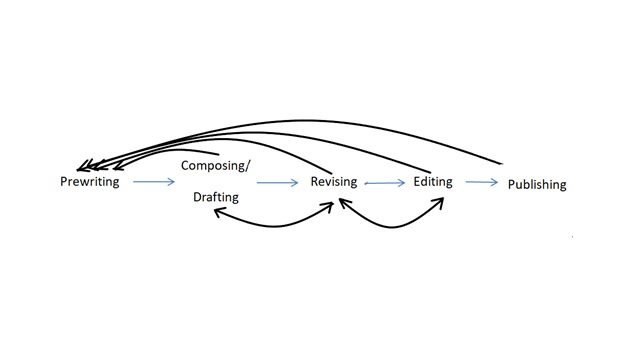

Lu (2013) states that the term process approach, originated from America, bases on the theory of cooperative learning. Cooperative learning theory, proposed by Slavin (1980, 2008), believes that cooperative learning is a learning technique encouraging students to work in groups to complete learning activities, receive recognition or get awards based on their group’s performance. This enables students to acquire language knowledge effectively and strengthen the relationship between teachers and students. A number of American linguistics and scholars (e.g. Flower & Hays, 1979; Stanley & Stevenson, 1985) have gradually demonstrated the theoretical and practical perspectives of the process approach. Nordin and Mohammad (2017) assert that process-focused approach is one of the best two approaches in teaching English writing. The other one is genre-focused approach. They (Nordin & Mohammad, 2017) describe the process-focused approach as a term which embraces a lot of practices and focuses on writing experiences rather than the final product. The process-based writing is a nonlinear, complex and recursive work because the writer (L2 learner) could go back to the first writing section once they have troubles in composing, revising, editing or publishing (Tribble, 1996). The language learner is the centre of process approach, a technique which not only emphases the position of learner’s cognition, but also pays attention to the teacher’s guidance. This teacher-centred approach has been discovered to receive increased attention because of little time spent on the teaching of writing and students’ active participation in learning activities (Scherer, 1984). Below is a holonomic graph explaining five steps of writing in process approach (Tribble, 1996):

(Picture 2)

Brainstorming can be seen one of the most essential factors in the process of writing, in which the English teacher primarily arouse students’ enthusiasm of thinking positively (Dovey, 2010). Students brainstorm and discuss useful vocabularies, grammar patterns, supporting ideas and arguments against the topic and any issues that they need to consider in writing. They also evaluate these ideas to see if all notes can be used in essay writing. In the drafting stage, the first draft of essay is produced which is usually done in groups (Hasan & Akhand, 2010). Students do draft exchange in the third section of writing process. During this part, learners read the draft produced by other peers and make comments on this product. After responding to other’s essay, students become aware of what contents should be included in a good essay (Hasan & Akhand, 2010) and make improvements on their own draft based on peer’s comments (Keh, 1990). Finally, those effective essays would be published to let writers receive comments from other readers. A good essay thus involves a process of searching for ideas, evaluating their value, critical thinking and well-organised structure, etc. (Shannon, 1994).

2.3 Analysis of writing stages in the process approach

A more comprehensive and systematic writing stage of process-focused approach is introduced by Tribble’s (1996), five stages of writing processes (prewriting, drafting, revising, editing and publishing).

2.3.1 Prewriting – nature of academic writing

The prewriting stage in academic writing, as well as the planning phase, is the beginning step in the process of writing where L2 writers (EFL/ESL students) gather and generate ideas (Bailey, 2015; Nation, 2008) by some typical activities like analysing writing titles (Mahnam & Nejadansari, 2012), brainstorming (Alodwan and Ibnian’s, 2014; Victori, 1999), quick-writing (Nation, 2008), and prepare an outline (Bailey, 2015). L2 writers are able to think, brainstorm and take notes surround the writing topic, shift direction to find a more satisfied alternative, and make a list of ideas to formulate an essay planning (Zamel, 1983). What is interesting is that some researchers (e.g. Franken, 1988) find that the number of grammatical errors is reduced dramatically if writers spend more time on planning ideas in advance. Keep asking questions (who, why, where, when) can also help to set steps in essay preparation and make all the important parts of the topic considered (Nation, 2008). Murray and Hughes (2008) argue that being organised in the writers’ way could be of greater assistance to themselves. For example, start writing essays by setting goals first, typical of these are opening an electronic file of their essay, sourcing the information, finishing the literature review, design their research instruments, collecting quantitative or/and qualitative data, completing data analysis and start to write the first draft. Goal setting can help writers to ensure their writing processes (Murray & Hughes, 2008) and the continuous completion of goals enables EFL/ESL writers improve their writing skills and build their confidence (Lim, 2003). Except for brainstorming and goal-setting, free-writing is another practical activity which normally exists in the prewriting stage. Its unpreparedness, unpredictablity and without time limitation encourage students to output knowledge with lower pressure and no worry about the quality of the output (Coffin, Curry, Goodman, Hewings, Lillis & Swann, 2005).

2.3.2 Drafting – nature of academic writing

Drafting is the physical act of writing (Richard & Rodgers, 2001), the real stage in which writers transform their ideas in minds or in notes on paper. This stage is also called as “translating” (Flower & Hayes, 1981, p.373), “organizing” (Victori, 1999, p.546) or “formulating” (Paltridge et al., 2009, p.21) phase as the second sub-process in academic writing. The information generated in the planning section could be represented in a variety of symbol systems such as graphs, tables and the elaborated syntax of written English (Flower & Hayes, 1981). To create a successful academic writing, skilled EFL writers always reorder their ideas discovered in the planning stage, add new ideas (Nussbaum & Schraw, 2007) and keep referring to the planned outline to see if they follow a linear and logical pattern once they proceed with their writing (Victori, 1999). Paltridge et al. (2009) explain that the second stage of writing aims to transform knowledge into a sequence of utterances, which requires more effort and time than that spent on the L1 writing. Some researchers advocate EFL/ESL students are supposed to focus on content rather than mechanics, especially expanding the notes (e.g. ideas, arguments and examples), rearranging utterances or paragraphs, and checking the coherence between sentence to sentence and paragraphs to paragraphs (Gabrielatos, 2002). Sometimes the action of composing sends L2 writers back to the planning phase while in some other cases it could be influenced by the feedback from teachers and peers (Tribble, 1996).

2.3.3 Revising – nature of academic writing

After completing the first draft, most of students would do some improvements to increase the quality of essays. These revising activities contain: adding, leaving out or changing ideas in the content; correcting lexical errors and so on, which exist at any stage in the writing process whether ideas have been written or not (Paltridge et al., 2009). It is interesting that both novice L2 writers and experienced L2 writers tend to pay more attention on fixing surface-level errors such as grammar mistakes and spelling errors instead of problems in the structure and the content (New, 1999). However, some empirical study (Victori, 1999) claim that it is far from enough to undertake global re-readings only in generating further ideas and proof-reading, good writers review their texts in a broad range of assessments: check whether the content has covered all the ideas in the outline in a logical order, evaluate the linguistic structures in the tests, keep sticking to the writing topic, and connect the relationships between sentence to sentence, paragraphs to paragraphs.

Some L2 writers also give distance from their academic essays and read their essays after leaving them for a few days. They can use both grammar checkers and dictionaries. Another strategy of revising their essays is to ask a native speaker for help to correct the errors in their essays.

2.3.4 Editing – nature of academic writing

Editing involves correcting the errors that showed in the revising stage like redrafting punctuation, spelling, grammar, sentence structure and accuracy of academic conventions such as the form of referencing and the organization of ideas (Poindexter & Oliver, 1998; Seow, 2002). Students are expected to edit their initial draft based on the feedback to ensure the accuracy of the content (Johnson, 2008). There are three main types of feedback happening in revision: peer feedback (Zhang. 1995), teacher feedback (Yang, Badger & Yu, 2006) and conference as feedback (Keh, 1990). Many researchers confirm that peer feedback and teacher feedback can reduce language errors in student essays (Diab, 2016), improve EFL/ESL students’ writing ability (Ruegg, 2015), and develop L2 learners’ language proficiency (Zhao, 2010). In particular, students may gain more scores on grammar and content with teacher feedback while more scores on organization and academic writing style with peer feedback (Ruegg, 2015). In conferences, teachers are more likely to be participants in the writing processes rather than grade-givers as teachers and students have interactive discussions during essay formulation and more accurate feedback are given during face-to-face interaction, which has a beneficial effect on both written and oral practice (Keh, 1990).

2.3.5 Publishing – nature of academic writing

As Poindexter and Oliver illustrate, “the purpose of publishing is to share and celebrate finished products” (1998, p.4). Publishing students’ finished products with other readers such as teachers, friends, peers and families can enhance the writing skills since the writer can communicate with readers to obtain more responses and also act as a role of reader to discover what readers may be interest in (Buhrke, Henkels, Klene & Pfister, 2002; Poindexter and Oliver, 1998). Johnson (2008) confirms that a cooperative and interactive environment allows students to share their ideas and suggestions, and get support from others. There are some suggestions made by Poindexter and Oliver (1998) for publishing the completed product such as classroom board and classroom newspaper to improve L2 writer’s confidence.

In conclusion, the main activities of the process approach were summarized as follow: In the prewriting stage, L2 writers always gather and generate ideas by some typical activities like analysing writing titles, brainstorming, quick-writing, and prepare an outline. In the drafting stage, skilled EFL writers always reorder their ideas discovered in the planning stage, add new ideas and keep referring to the planned outline to see if they follow a linear and logical pattern once they proceed with their writing – focus on content rather than mechanics, especially expanding the notes (e.g. ideas, arguments and examples), rearranging utterances or paragraphs, and checking the coherence between sentence to sentence and paragraphs to paragraphs. In the revising stage, good writers review their tests in a broad range of assessments: check whether the content has covered all the ideas in the outline in a logical order, evaluate the linguistic structures in the tests, keep sticking to the writing topic, and connect the relationships between sentence to sentence, paragraphs to paragraphs. Editing involves correcting the errors that showed in the revising stage and rewrite the first draft with the feedback. In the publishing stage, the writer can communicate with readers to get more significant responses and also act as a role of reader to discover what readers may interest.

2.4 Previous studies on two writing processes in ESL/EFL context

Since 1960s, the product approach which derives from the theory of behaviourism has been widely used in all over the world (Yang, 2016). It relies much on linguistic knowledge, for example grammar and text structures (Badger & White, 2000). The learning activity often taking place in English teaching classroom in the 1960’s, was sentence drilling (Yang, 2016), in which students try to create new sentences by combining the given sentence model with the social context of the topic. Until 1970s, the teaching mode transferred from sentence drilling to discourse level (Thulasi et al., 2015) and teachers adopt controlled composition tasks to help students manipulate certain grammar and discourse structure in English writing (Badger & White, 2000; Thulasi et al., 2015).

The model essay (nature of academic writing) can be regarded as the key of product approach which has been discussed from different perspectives about its advantages in improving students’ writing skills (Thulasi et al., 2015) and their writing performances (Saeidi & Sahebkheir, 2011). Thulasi et al. (2015) argue that many Malaysian English teachers still use product method in EFL/ESL classroom in spite of its opposite results (e.g. inflexible) that learners may ignore the process of creating writing. They (Thulasi et al., 2015) reviewed an extensive range of existing literature to investigate the issues behind the situation and reveal the reasons why this mechanical training still has its dominant position in English teaching in the context of Malaysia. The preference of the product approach over the process approach could be related to large class sizes, efforts to cover all learning activities on syllabus and much easier to give direct feedback to save time, etc. In addition, Thulasi et al. (2015) also state that “teachers must provide students with new strategies such as creative writing, self-evaluation and critical analysis practices” to help students writing effectively (p.56). These new strategies recommended by Thulasi et al. are parts of components of process approach.

Compared with lexico-grammatical areas in the product approach (Pasand & Haghi, 2013), linguistic skills have been highlighted in the process approach. Many researchers (e.g. Bruton, 2005; Hasan, & Akhand, 2010; Kolade, 2012; Nordin & Mohammad, 2017) support that the process approach is a major revolution or new breakthrough over the traditional product-focused approach with many advantages. In the process approach, the English teacher acts as a facilitator and a reader to guide students to generate ideas, integrate the topic in writing, revise ideas in the second or third draft (could be more than three) and give feedback (Nordin & Mohammad, 2017). Proponents of this student-centred approach assert that it is a non-linear repeated process complexity of which could be of assistance to writers’ (i.e. students in writing classes) performances and their writing skills (Kolade, 2012). 80 Nigerian senior secondary school bilingual students in their last year were involved in Kolade’s research that comprised a controlled group and an experimental group with pre-test and post-test. The research materials were the textbook that recommended by senior secondary school, English language syllabus of National Examination Council and West Africa Examinations, the curriculum from Federal Ministry of Education, lesson notes from English teachers, and exercise books of students essay writing. The results of Kolade’s study indicate that process approach permitted students to discover and reorganise their ideas to produce a more appropriate written product. Effective intervention in writing process (for example, the stage of revising or giving feedback) offered an extensive exposure to information of the topic and repetitive editing provides an opportunity to practice students’ writing skills (Kolade, 2012).

2.5 Research gap

With regard to the effect and implication of the product approach and the process approach, research had been done on Chinese primary students (Ho, 2006), senior students (Lu, 2013) and undergraduate students (Prosser & Webb, 1994; Wei, 2007) separately, which demonstrated that to some extent Chinese English writing classroom was occupied by the product approach. Besides, the process approach had been evaluating with the integration of the product approach which had earned the dominant position in the context of China. For example, Ho (2006) compared the results of students from both lower primary school level and high primary school level through pre-test and post-test and drew conclusion that the process approach seemed to be an effective approach even in the lower primary school level and process-oriented writing could enlighten students writing ability and confident of students. But these results were not valid because Ho only adopted a single research method to explore the experience of writing a very short composition.

The present study (nature of academic writing) was designed to fill this gap to investigate the experience of writing academic essays in terms of the process approach to see whether Chinese international students, whose English language level was similar, could benefit from applying the process approach in their English essay writing. The merit and demerit of the product approach and the process approach would be elaborated to figure out how to combine these two writing approaches in English writing classroom.

In this chapter, the theoretical background of the product and process approach was introduced, including general writing stages of both approaches. Furthermore, the specific writing phases of the process approach have been demonstrated in five sections: planning, drafting, revising, editing and publishing. L2 writers analyse the writing topic, consult relative information through published materials, prepare outline and content structure in advance, take notes while reading references and do free-writing in the planning stage. Some researchers suggest that more attention should be paid on the content instead of lexical knowledge while composing, such as adding new ideas, expanding the notes, reorder the arguments in the essays and checking coherence and cohesion. After finishing the first draft, L2 writers revise and edit the first draft to strengthen the quality of their essays, which leads to the final stage publishing to improve their writing skills by communicate with other readers to get suggestions.

For these participants, their English teachers in secondary schools and universities usually use the traditional writing approach in teaching English writing mainly as massive tasks need to be completed in a limited period of time. Process-oriented writing approach is time-consuming which is not realistic to adapt in Chinese context because of large class size and lack of time, but it is quite popular for Chinese students who study abroad in higher education to understand nature of academic writing.

Chapter 3: Methodology (Nature of academic writing)

This chapter aims to explain the research methodology, discuss how to analyse quantitative and qualitative data, and introduce the instruments adopted in the pursuit of the goals of the research. In addition to research methodologies, this chapter also presents a detailed account of the pilot study and how it helped in refining the research instruments. It also describes the data collection and analysis for both pilot study and main study.

3.1 Research questions (Nature of academic writing)

The study was designed to discover which writing approach Chinese international students prefer to use in the process of essay writing and to ascertain any relationship between writing approach preferences and writing confidence, particularly the relationship between the process approach and their writing confidence. The research questions of the study are:

- In what ways do Chinese PG students describe how they have been taught to write essays during their schooling?

- How do Chinese PG students characterise their experiences of essay writing now as overseas students?

- Which methods do Chinese PG students use in their essay writing in English?

- What do they perceive to be the challenges and benefits of these processes?

3.2 Participants (Nature of academic writing)

The participants of questionnaires in this study were 60 Chinese international students in the Department of Education in a UK university. All participants were Chinese native speakers. Before entering university for their master degree, all participants had already studied English for almost ten years, more than five hours each week on the average. After taking English language tests such as IELTS (6.5+) demonstrated their English language levels, they were enrolled in a university in the UK. In addition, most of participants had been studying English academic essay writing for almost one year when they took part in this study.

As for the participant of the interviews, a sample of 10 Chinese overseas postgraduates volunteered to take part in the interviews after they had done the questionnaire. These interviews were conducted in Chinese language, tape-recorded, transcribed and then translated into English. Those 10 students were asked to elaborate their opinions about the writing approach use in composing academic essays.

3.3 Research models (Nature of academic writing)

In this study, the framework of present questionnaire was extracted by Petrić and Czárl’s (2003) Validating Writing Strategy Questionnaire with some adjustments on items. The aspects of statements in the final questionnaire were determined by Gabrielatos’ (2002) A Framework of Product-oriented and Process-oriented Approaches including the features of the product and process approach.

Items in this questionnaire were adopted by Petrić and Czárl (2003) who also used triangulation of different data sources studying the potential factors that could affect participants’ responses in relation to writing strategies. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, Petrić and Czárl (2003) presented various writing stages in the process of validating a writing strategy questionnaire and a list of written statements describing the use and frequency of writing strategies.

According to Gabrielatos (2002), there were two elements of good writing in the EFL context: “product” (p.5) and “process” (p.6). He explained several aspects that should be contained in these two categories: “language, layout and organization, relevance to the task, regard for the reader, and clarity” (2002, p1) for the product section and “task/title analysis, planning, writing the first draft, evaluating and improving the first draft, and language problems versus writing problems”(2002, p1) for the process section. This well-structured organization about the product and process approach provided the research framework for the present questionnaire.

Alodwan and Ibnian (2014) examined what essay writing skills that university students need in EFL contexts and how the process approach helps university students develop their writing skills in English essay writing. They classified (2014) several main features of the process approach which were also showed in the present questionnaire after evaluating with the aspects of good writing by Gabrielatos (2002).

3.4 Research method (Nature of academic writing)

For the purpose of this study, a mixed research method was used. Chinese international students’ preferences of writing approaches in HE were revealed by a questionnaire and interview. Both quantitative data and qualitative data integrated in a single study to validate the research, which increased strengths while reducing weaknesses (Dornyei, 2007). This was further emphasized by the factor that the strengths of one research method could be utilized by overcoming the weaknesses of the other research method in one study. For example, some researchers (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2002) maintained that the quantitative research compared similarities among a large number of samples to look at frequencies of a phenomenon by counting numbers. All the quantitative methods aimed at specifying the relationships amongst variables to capture certain features of quantitative research (Dornyei, 2007), which might ignore some exceptions that required special attention (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). This problem could be fixed by adopting qualitative research methods, such as the interview, to explore the nature of uniqueness to validate quantitative data (Creswell& Creswell, 2017).

Given these, this study was made of quantitative research (a 68-item questionnaire) and qualitative research (semi-structured interviews) to identify writing approaches, and to reveal the merits and demerits of approaches employed by Chinese international HE students (see Appendix A). The questionnaire was divided into two parts: students’ attitudes towards the writing approach which was taught in their early schooling (from Item Pre 1 to Pre 4) and writing activities of the process approach. Students’ knowledge about the two approaches and the effectiveness and challenges of them were examined in the interview. Quantitative data, at first, were collected and analysed providing a general understanding of research questions, and then qualitative data were collected and analysed explaining those statistical results by exploring participants’ view in depth (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

3.4.1 The questionnaire – nature of academic writing

Previous studies such as Gabrielatos’ (2002) A Framework of Product-oriented and Process-oriented Approaches, Alodwan and Ibnian’s (2014) Development of EFL University Students Essay Writing Skills by Using the Process Approach and Petrić and Czárl’s (2003) Validating Writing Strategy Questionnaire were used in designing the questionnaire in this study. All questionnaire items were adopted by Petrić and Czárl (2003) who also used triangulation of different data sources studying the potential factors that could affect participants’ responses in relation to writing strategies. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, Petrić and Czárl (2003) presented various writing stages in the process of validating a writing strategy questionnaire and a list of written statements describing the use and frequency of writing strategies.

In order to discover the essay writing process of Chinese overseas students in HE and how many writing activities they have gone through in their essays writing, an instrument (a 68-item questionnaire) was developed to measure whether the completion of writing stages has a relationship with students’ writing confidence. It is acknowledged that the questionnaire is one of the most common research instruments applied in educational (Cohen et al., 2002) and social research (Dornyei, 2007) because the questionnaire is relatively easy to design and quickly to gather a large amount of research data in a fixed form (Dornyei, 2007).

For 68 items of each questionnaire, students were asked to click one option of 5 choices of Likert Scale, describing to what extent Chinese overseas students agree with the statements (strongly disagree; disagree; neutral; agree; strongly agree). Each option was coded in a numerical value. For example, the strongest negative option (strongly disagree) was coded as 1 and the strongest positive option (strongly agree) was coded as 5. This questionnaire was in Chinese. Chinese overseas postgraduate students’ responded to the preparation of essay writing and the usage of writing activities in the process approach were evaluated by using a 68-item questionnaire focusing on students’ behaviours during essay writing. It was a structured questionnaire that took no more than 10 minutes to complete. The 68-item inventory was divided into two parts: attitudes to the writing approach that they have experienced in China and the activities that they used in their essay completion. Four statements (Item 1 to Item 4) were included in the attitudes towards the previous writing approach in the first part of the questionnaire. The writing activities part contained three sections: prewriting section (10 statements, from Pre1 to Pre10), drafting section (10 statements, from D1 to D10), revising section (15 statements, from R1 to R15), editing section (6 statements, from E1 to E6) and publishing section (2 statements, P1 and P2). The prewriting scale items focused on the preparation activities before starting to write, for example, brainstorming, writing plan and communicative activities. Items in the drafting section described the processes of ideas transformation, from ideas in mind or ideas inspired by other authors into texts. Revising section explained what errors that writers correct when they revise and the solutions when they are confronted of the problems. Statements in the editing stage were about the types of feedback that writers could use in producing a new draft. The publishing section addressed how Chinese overseas students feel about publishing their written essays. The questionnaire was design in this way that different writing activities applied in each stage of writing process could be readily evaluated and analysed.

3.4.2 The interview – nature of academic writing

In addition to the questionnaire, the other research instrument employed in this study is semi-structured interview as Dornyei (2007) and Cohen et al. (2002) state that the interview is one of the most frequently used qualitative research techniques. It is also a powerful means for researchers to supplement the former questionnaire survey since a single research method can merely examine a social phenomenon in a more depth and questionnaire survey has its inherent weakness that questionnaire only offers a general understanding of research questions so that researchers cannot explore complex problems deeply (Bryman, 2016). There are three main types of interview categorized by questions’ flexibility: structured interview, semi-structured interview and unstructured interview (Cohen et al., 2002). In this study, semi-structured interview was used in conjunction with the former questionnaire to follow up unexpected answers that appeared in the quantitative data. The interview validated this questionnaire and dug deeper into the reasons why Chinese international students prefer the process approach in academic essay composing (Cohen et al., 2002).

The interviews included 5 main questions about participants’ perspectives of the effectiveness of the process approach in English essay writing and the classroom activities related to the process approach. First, interviewees needed to describe how they compose an essay when they attended schools in China and compared these writing experiences with that in the UK. Second, they shared their evaluation of these writing activities that experienced in Chinese writing classroom. Then, answer the question that if these writing activities that they experienced in China provided any help for their English writing. After that, reporting their perspectives of the processes that they wrote their academic essays in the UK. Finally, demarcating the writing approaches they applied in their essay writing in the UK and stated the challenges and benefits of the approaches they applied in their essay writing in the UK.

3.4.3 Pilot study – nature of academic writing

As Dornyei (2007) said, a research study also needs a rehearsal to ensure the validity and reliability of the results in the specific context, the pilot study was conducted to refine and modify the questionnaire and the interview. He (Dornyei, 2007) also notes that “field testing”(p.112) is essential in the developments of research instruments, that is, piloting the research instruments (the questionnaire and interviews of this study) with a sample of population which is similar to the target people that these instruments are designed for. So the questionnaire had been piloted before administering in the main study with a sample of Chinese postgraduate students who were studying in a certain university in the UK.

Petrić and Czárl’s questionnaire (see Appendix) was used as the pilot questionnaire with 50 participants in the previous study and a five-point Likert Scale was adopted. In the process of piloting, there were several items that were not quite related to the process approach so that this kind of items was deleted. For example, the meaning of “model” in item 3 of Petrić and Czárl’s questionnaire was questioned by several participants. After explaining the meaning of this word, item 3 was taken off in the main study, because the model sample is the centre of the product approach instead of the process approach. There was another problem that participants were confused about the condition where item 1 happened. Students made the timetable based on the supervisor’s requirement. So in the main study, this item (P1) was adapted as I make a timetable for the writing process no matter it is requested by my supervisor.

3.5 Ethics

Consent forms for the questionnaire and interviews were attached before conducting the online questionnaire and face-to-face interviews which detailed the purpose of this study, the confidentiality and their rights to withdraw the questionnaire and interview at any time. Because interviewees were chosen by emailing them to investigate the unusual responses to some items in the questionnaire, so this study was not anonymous. Once participants agreed with this form, they were able to do the following questionnaire and interviews. All 60 participants volunteered to do online questionnaire. Participants in the semi-structured interviews were also informed that their responses could be audio-recorded and then transcribed into written forms. The potential use of quotations of their words was also shared with them and agreed by every interviewee. All the questionnaires, interview recordings, and transcriptions were stored in locked files, which could only be accessed by the researcher. None of them would be identified individually.

Chapter 4: Results (Nature of academic writing)

This chapter presents the results and findings of this study in four research questions. The first two sections report the description of writing processes that Chinese HE international students experienced in China and in the UK separately. Secondly, it presents the frequency of the usage of the product and process approach through the analysis of the results from both quantitative data and qualitative data in the third section. Finally, it reveals students’ perceptions of the application of the product and process approach by analysing the qualitative data of the interviews with students.

4.1 In what ways do Chinese PG students describe how they have been taught to write essays during their schooling

The whole percentages of students’ attitudes towards English writing were collected and tabulated in Table 4.1.1. These frequency tables presented the extent to which students enjoy the product approach in English writing.

Table 4.1.1 Percentage of responses to the items of the writing approach they have been taught in China

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Pre 1: I like writing. | 13.30% | 40.00% | 25.00% | 13.30% | 8.30% |

| Pre 2: I like the writing lessons in school. | 5.00% | 13.30% | 31.39% | 32.30% | 18.01% |

| Pre 3: I think writing is interesting. | 15.32% | 32.19% | 17.89% | 27.90% | 6.70% |

| Pre 4: I have confidence in writing in English. | 11.38% | 46.77% | 17.70% | 14.58% | 9.57% |

Table 4.1.2 Percentages of all Part A statements

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Percentage % | 11.25 % | 33.07% | 23.00% | 22.02% | 10.65% |

As shown in Table 4.1.2, Chinese overseas students in the UK were quite negative in their attitude towards the English writing experiences in secondary and high school. Almost half of students for choosing disagree and strongly disagree (44.32%) in these four items felt that they did not enjoy the product writing approach in secondary and high schools. The percentage for agree and strongly agree was one third of the whole number of participants (32.67%). When it comes to a writing topic that is similar to the topic of the sample text, students reported that they were able to use the model lexical structures in the process of producing a written text, which is time-saving.

Interview data explained the reason why international students had a negative attitude to the product approach in improving writing skills. Three interviewees stated that English writing lessons were very boring as teachers always taught grammar and vocabulary knowledge by correcting lexical errors of English compositions in writing class which had no differences between the English grammar lessons. One interviewee also said, “I think there is another reason that English teachers teach less about how to compose a written product and it is challenging for students at schooling age to get ideas from prior knowledge and organise these ideas into a written draft.” In this sense, they believed the product approach did little help to compose essays in HE. However, one participant gave an opposite answer to this statement. He demonstrated, “I think the model sample is very useful, at least it helps me start the writing journey when I am totally lost in reading references … And for EFL/ESL novices, vocabularies, phrases, and grammar and sentence patterns in model sample were of great help in composing which easily let learners complete a composition and release them from the written tasks.” This indicated that the traditional writing approach not only helped participants get inspirations but also helped lower-level English learners to reduce the anxiety and build confidence. A few number of interviewees among the 22.92% for neutral commented that they did not remember the experience of English writing lessons in China. Others who held neutral position implied they did not apply the product approach in essay writing since sometimes they just translated the ideas from Chinese to English and wrote them down without organizing these ideas logically.

Table 4.1.3 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ writing attitude towards English writing before students study abroad.

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | |

| Mean | 2.63 | 2.78 | 2.58 | 2.10 |

| Median | 2.50 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Mode | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Standard deviation | .956 | .940 | 1.030 | .877 |

| N valid | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Table 4.1.3 presents the mean, median, mode and standard deviation of participants’ choices of writing attitudes. The mean scores of these four items fluctuated between 2 (Disagree) and 3 (Neutral), indicating the attitude of Chinese international students was quite negative in English writing. The mode for Item 2 (I like the writing lessons in school) was 4 (Neutral), suggesting that Chinese English learners were motivated in writing English. These results indicated that although some students did enjoy the process approach at home, most of Chinese overseas students had a negative attitude towards English writing lessons in China because of several reasons.

4.2 How do Chinese PG students characterise their experiences of essay writing now as overseas students

Research Question 2 asked students’ experience of writing English academic essays in the UK. The answers of Chinese postgraduate students showed that all students in HE experienced at least four stages of the process-oriented writing process from essay preparation to essay editing.

4.2.1 Responses to items of the planning stage – nature of academic writing

Table 4.2.1.1 demonstrates what prewriting activities students prefer to do when they compose essays.

Table 4.2.1.1 Students’ prewriting activities

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Pre 1: I make a timetable for the writing process no matter it is requested by my supervisor. | 3.30% | 0.00% | 25.00% | 58.30% | 13.30% |

| Pre 2: I brainstorm to generate ideas. | 5.00% | 3.30% | 5.00% | 58.30% | 28.30% |

| Pre 3: I write without a written plan. | 21.70% | 68.30% | 5.00% | 3.30% | 1.70% |

| Pre 4: I plan out the organisation in advance. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 11.70% | 56.70% | 28.30% |

| Pre 5: I plan out the organisation as I go. | 1.70% | 20.00% | 20.00% | 46.70% | 11.70% |

| Pre 6: I consult references for more information about my topic. | 1.70% | 1.70% | 5.00% | 51.70% | 40.00% |

| Pre 7: I think of the relevance of the ideas. | 0.00% | 0.00% | 10.00% | 60.00% | 30.00% |

| Pre 8: I discuss my topic with my friends. | 3.30% | 3.30% | 30.00% | 38.30% | 25.00% |

| Pre 9: I discuss my topic with my tutors. | 0.00% | 5.00% | 15.00% | 45.00% | 35.00% |

| Pre 10: I ask my classmates about the strategies they use in their writing activity that may help me. | 1.70% | 0.00% | 20.00% | 45.00% | 33.30% |

For the organization of their essays (Pre1, Pre3, Pre4 and Pre5), most of participants agreed to that they produced a written plan (90.00%), brainstormed ideas (86.6%) and made a timetable for the writing process (71.60%) during the creation stage. However compared with the number of those who planned out the organization in advance (85.00%), only half of them (58.40%) prepared the essay’s organization as they wrote, which indicated that Chinese L2 learners who studied in the UK preferred to have a clear organization before writing their essays. Three items (Pre2, Pre6, and Pre7) were to discover how Chinese international students in HE arrange their content of academic essays in the prewriting stage. Consulting references in the library or online was the most common method to generate ideas (91.70%), followed by the brainstorming activity (86.60%). 90% of participants also considered the relevance of the ideas that would be concluded in their drafts. When students had problems in evaluating writing topics, there were normally two solutions: communicate with their supervisors and discuss with peers. A large number of participants (80.00%) chose to discuss with their tutors for professional and useful suggestions to solve these problems while less participants (63.3%) had cooperative interactions with their friends. Sometimes peer conversation inspired them to get started.

To reveal how many process activities in the planning phase that participants used to compose academic essays, the total score, mean and standard deviation were calculated (see Table 4.2.1.2).

Table 4.2.1.2 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ preparation activities in the planning stage.

| Pre1 | Pre2 | Pre3 | Pre4 | Pre5 | Pre6 | Pre7 | Pre8 | Pre9 | Pre10 | |

| Mean | 3.78 | 4.02 | 1.95 | 4.10 | 3.47 | 4.27 | 4.20 | 3.78 | 4.10 | 4.08 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Standard deviation | .804 | .965 | .746 | .730 | .999 | .778 | .605 | .976 | .838 | .829 |

| N valid | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Note: the scores of Item Pre3 need to be recoded because Pre3 is negative utterance.

From the mean score of each item, around 4.00 (from 3.47 to 4.27), similar responses to the completion of prewriting activities could be found. A number of participants agreed and strongly agreed with the statements in the planning stage of writing processes. Participants analysed writing topics, used brainstorming activity, prepared an outline in advance, and sought for help from supervisors and peers when they faced with topic issues.

4.2.2 Responses to items of the drafting stage – nature of academic writing

Table 4.2.2.1 presents the drafting activities that Chinese HE overseas students could do in composing their essays.

Table 4.2.2.1 Students’ drafting activities

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| D1: I write the introduction first. | 3.30% | 15.00% | 23.30% | 41.70% | 16.70% |

| D2: I think of the suitability of expressions I used. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 5.00% | 66.70% | 26.70% |

| D3: I use some familiar expressions in order not to make mistakes. | 3.30% | 21.70% | 26.70% | 31.70% | 16.70% |

| D4: I use some examples to explain the meaning when I cannot find the exact expressions. | 1.70% | 11.70% | 15.00% | 51.70% | 20.00% |

| D5: I discuss various points of view in my writing. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 10.00% | 65.00% | 23.30% |

| D6: I produce subsequent drafts. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 16.70% | 38.30% | 41.70% |

| D7: I periodically check whether I am keeping to my topic. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 10.00% | 65.00% | 23.30% |

| D8: I periodically check whether my writing is making sense to me. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 8.30% | 61.70% | 28.30% |

| D9: I discuss with my tutors when I have writing problems. | 1.70% | 1.70% | 10.00% | 51.70% | 35.00% |

| D10: I discuss with my classmates when I have writing problems. | 1.70% | 1.70% | 11.70% | 58.30% | 26.70% |

As shown in Table 4.2.2.2 the responses to the drafting items, almost more than 90% participants asserted that they experienced all the activities included in the drafting stage. However, there are three significant numerical changes compared with those percentages in the third column (Disagree). The figures for Disagree of all drafting items were less than 5%, but the percentages of item 1 (D1), item 3 (D3) and item 4 (D4) were more than 10%. Almost one quarter of the participants (21.70%) disagreed with the statement (D3) that I use some familiar expressions in order not to make mistakes.

One interviewee described the reason why I do not write the introduction first was the significance of the introduction, “… personal viewpoints to the writing topic also should be included in the introduction which cannot be certain until I finish the main body of the writing assignment. It is convenience for me to complete introduction and conclusion after finishing the main body parts of the whole essay.” Two interviewees also maintained that one of the key elements of an effective introduction was describing the background of the writing topic, and the writer may be able to provide a well-developed writing background once he/she finished the main part of the essay. Those participants who preferred to write the introduction at the end indicated a strong connection between the introduction and the main body of the essay, considering the role of the coherence and cohesion. When it comes to item D3 (I use some familiar expressions in order NOT to make mistakes), some of interviewees would look up the dictionary, discuss with friends and confer with supervisors to make sure the correction of the expressions in the essays. Others said they were more likely to rely on the feedback from their proof-readers. When participants (11.70%) cannot find the exact expressions in their language corpus as presented in Item D4 I use some examples to explain the meaning when I cannot find the exact expressions, a common solution to deal with this problem that they reported was to skip to another similar points of ideas so that writers could avoid making mistakes and have confidence about their written product. A few interviewees suggested they would even change their viewpoints to an easier area if they did not know the exact expressions.

Table 4.2.2.2 concluded the numerical information about the usage of drafting activities.

Table 4.2.2.2 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ writing activities in the drafting stage.

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | D10 | |

| Mean | 3.53 | 4.18 | 3.37 | 3.77 | 4.08 | 4.18 | 4.10 | 4.17 | 4.17 | 4.07 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Standard deviation | 1.049 | .596 | 1.104 | .963 | .696 | .833 | .630 | .642 | .806 | .778 |

| N valid | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

The standard deviation of item D2 (SD=.956), D5 (SD=.696), D7 (SD=.630) and D8 (SD=.642) were quite lower in comparison with other results, which means that responses to D2, D5, D7 and D8 were very similar. It is noticeable that the mode for item D3 I use some familiar expressions in order NOT to make mistakes was 2 suggesting that Chinese HE international students were not afraid of making mistakes because they would do revision and editing after the first draft was completed, as stated by 5 interviewees.

4.2.3 Responses to items of the revising and editing stages

Activities in the revising and editing stages always overlap because writing problems found in the revision needed to be modified in the editing stage. Table 4.2.3.1 and Table 4.2.3.2 were the results of statements in the revising and editing stages.

Table 4.2.3.1 Students’ revising activities

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| R1: I use a dictionary to make sure of my wording and usage. | 1.70% | 0.00% | 11.70% | 46.70% | 40.00% |

| R2: I use spell-checkers. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 11.70% | 48.30% | 36.70% |

| R3: I use grammar checkers. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 13.30% | 51.70% | 33.30% |

| R4: I check whether I have written everything I wanted to say. | 1.70% | 3.30% | 10.00% | 50.00% | 35.00% |

| R5: I check whether more examples are needed. | 0.00% | 5.00% | 21.70% | 48.30% | 25.00% |

| R6: I check whether more explanation is needed. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 15.00% | 56.70% | 25.00% |

| R7: I check whether the organisation of my writing is clear. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 6.70% | 55.00% | 36.70% |

| R8: I check my sentence structure. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 13.30% | 50.00% | 33.30% |

| R9: I check whether the sentences in the paragraph are connected. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 10.00% | 58.30% | 28.30% |

| R10: I check whether the main ideas are referred to in the conclusion. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 11.70% | 46.70% | 38.30% |

| R11: I check my punctuation. | 0.00% | 6.70% | 18.30% | 45.00% | 30.00% |

| R12: I check my spelling. | 0.00% | 0.00% | 11.70% | 55.00% | 33.30% |

| R13: I check whether I have used academic English conventions, e.g., formality and referencing. | 0.00% | 1.70% | 13.30% | 45.00% | 40.00% |

| R14: I check to make sure that I have met the requirements of the writing activity. | 0.00& | 1.70% | 6.70% | 55.00% | 36.70% |

| R15: I give the draft to others for proofreading. | 0.00% | 8.30% | 20.00% | 46.70% | 25.00% |

Table 4.2.3.2 Students’ editing activities

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| E1: I revise the draft to clarify the meaning. | 1.70% | 3.30% | 11.70% | 55.00% | 28.30% |

| E2: I edit the draft myself. | 0.00% | 0.00% | 6.70% | 53.30% | 40.00% |

| E3: I leave the text for a while and then read it again later. | 0.00% | 6.70% | 21.70% | 46.70% | 25.00% |

| E4: I edit the draft based on the peer’s feedback. | 8.30% | 3.30% | 20.00% | 48.30% | 20.00% |

| E5: I edit the draft based on the teacher’s feedback. | 1.7% | 6.70% | 16.70% | 51.70% | 23.30% |

| E6: I edit the draft based on the feedback from proofreading. | 5.00% | 18.30% | 38.30% | 25.00% | 13.30% |

Students always revised mechanical problems themselves, for example spelling and grammar errors as showed in Table 4.2.3.3 (Item R12 I check my spelling, Mean=4.22, SD=.640) and Table 4.2.3.4 (Item E2 I edit the draft myself, Mean=4.33, SD=.601).

Table 4.2.3.3 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ writing activities in the revising stage.

| Mean | Median | Mode | Standard deviation | N valid | |

| R1 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 4 | .789 | 60 |

| R2 | 4.18 | 4.00 | 4 | .770 | 60 |

| R3 | 4.17 | 4.00 | 4 | .717 | 60 |

| R4 | 4.13 | 4.00 | 4 | .853 | 60 |

| R5 | 3.93 | 4.00 | 4 | .821 | 60 |

| R6 | 4.03 | 4.00 | 4 | .736 | 60 |

| R7 | 4.27 | 4.00 | 4 | .660 | 60 |

| R8 | 4.13 | 4.00 | 4 | .769 | 60 |

| R9 | 4.12 | 4.00 | 4 | .715 | 60 |

| R10 | 4.20 | 4.00 | 4 | .777 | 60 |

| R11 | 3.98 | 4.00 | 4 | .873 | 60 |

| R12 | 4.22 | 4.00 | 4 | .640 | 60 |

| R13 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 4 | .745 | 60 |

| R14 | 4.27 | 4.00 | 4 | .660 | 60 |

| R15 | 3.88 | 4.00 | 4 | .885 | 60 |

Table 4.2.3.4 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ writing activities in the editing stage.

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | |

| Mean | 4.05 | 4.33 | 3.90 | 3.68 | 3.88 | 3.23 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Standard deviation | .832 | .601 | .858 | 1.097 | .904 | 1.064 |

| N valid | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

4.2.4 Responses to items of the publishing stage

For the perspective of publishing completed essays, more than 90% of HE students preferred to see their final draft to be published (Mean=4.30/3.92, SD=.696/.962).

Table 4.2.4.1 Students’ publishing activities

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| P1: I prepare a final, polished draft. | 0.00% | 3.30% | 3.30% | 53.30% | 40.00% |

| P2: I love to see my essays to be published. | 1.70% | 10.00% | 10.00% | 51.70% | 26.70% |

Table 4.2.4.2 Mean, mode, median and standard deviation of students’ writing activities in the publishing stage.

| P1 | P2 | |

| Mean | 4.30 | 3.92 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 4 |

| Standard deviation | .696 | .962 |

| N valid | 60 | 60 |

4.3 Which methods do Chinese PG students use in their essay writing in English

Almost all interviewees confirmed that in most cases they used the process approach and experienced all writing stages except publishing in composing the academic essays. They even concluded some suggested writing activities that they could apply in the next writing task.

One of these interviewees reported that “Before writing, consulting the conferences in the library is the main source for me to gather ideas, because it is very convenience for international students to look through relative articles and books via online library and we do not need to carry paper book all around. Another advantage of consulting other writers’ products is that massive information has been summarized and expounded in their writings whose writers are experts in their researching filed and the reference list attached at the end of the articles and books also introduces the information in relation to a certain topic”. “Sometimes brainstorming does great help for me to start to write, which could enhance the confidence because I have already learned the knowledge that I used in brainstorming”, mentioned by another interviewee. Model texts in the product approach also played a significant role in formulating students’ essays especially when they did not know a certain writing area and model samples could provide related vocabularies, grammar and sentence patterns that students used in their essays. If L2 writers had difficulties in analysing the writing topic, they were able to discuss with other people like friends and supervisors. Once starting to compose, the focus needed to be placed on the content to see whether writers included all the ideas in the written plan. After completing the first draft, students revised the first draft by themselves, or with their peers, supervisors and local native speakers for proofreading. Finally, edit the draft with given feedback and prepare a completed written version.

The writing experiences that interviewees stated were similar to the statements in the present questionnaire, which means Chinese international students in this study tended to employ the process approach while writing their academic essays with model texts functioned as a technique for inputting the language knowledge.

4.4 What do they perceive to be the challenges and benefits of these processes

Interviews also investigated students’ perceptions of challenges and benefits of the product and process approaches. All interviewees demonstrated that product approach was useful for them to practice their writing by imitating model samples particularly for L2 novices. 7 interviewees expressed that analysis of the model sample provided sufficient language input such as genre vocabulary, grammar and sentence structures, since it provided them with knowledge to practise their writing under the English teacher’s clear instructions, which helped them build confidence once they completed a final composition and improve students’ writing in a short period. However, 3 interviewees still claimed that the product approach relied too much on surface language level which made no differences with other lessons where teachers teach new vocabulary and grammar knowledge. This would reduce students’ enthusiasm in learning second foreign language if the class was boring. “Another problem is lack of communicative content”, mentioned by one interviewee, “overemphasis on linguistic knowledge makes L2 writers ignore their role of being a reader which is an essential factor of an effective essay”.

The proponents of the process approach proposed that writing was integrated with communicative tasks. It improved both written English and oral English, and enabled them to experience various parts of writing processes and write freely in target language. The face-to-face guidance in the revising stage offered more accurate and precise feedback than those in the product approach. As for its disadvantages, the biggest problem for the process approach was classroom disorder. 4 interviewees described in Chinese context, it was common see that the size of a classroom is more than 60 students. Since the process approach was time-consuming, it was not realistic for English teachers to adapt the process approach in Chinese big-size classroom with time limitation and tasks needed to finish in the teaching curriculum. Besides, brainstorming was one of the most important prewriting activities in the process-oriented approach which required much background knowledge, but it could only be useful when adopted among higher-level English learners, because “most of L2 novices were not equipped with solid knowledge to run this activity” as proposed by one interviewee.

Chapter 5: Discussion – Nature of academic writing

The present chapter discusses the findings in this questionnaire and interview comparing with previous literatures. The questionnaire aims to explore students’ attitudes to the writing approach applied in their English classroom in China and discover writing activities in the process approach. Semi-structured interviews were carried out to look into the reasons for unusual responses to the questionnaire items and probe the advantages and disadvantages of the process approach in HE essay writing.

5.1 Interpretations of the product approach

The first two research questions were investigated by the questionnaire about the experience of the product approach and the process approach. Part A of the questionnaire was to reveal the experience of the product approach in students’ schooling ages by defining 4 statements associated with the language level of English (Pre1), the implication of the product approach in L2 classroom (Pre2), writing skills that they had acquired (Pre3), and whether they were able to adapt the product approach flexibility in English composition (Pre4). These items were related to the first research question ‘in what ways do Chinese PG students describe how they have been taught to write essays during their schooling’. This study found, although some students enjoyed learning English writing in the product approach in relation to their previous experiences, the number of students who showed disagree and strongly disagree could not be ignored. The mean score for the attitude of the traditional product approach indicated that these Chinese international students were not very confident in using the product approach in writing long academic essays. The findings were in accordance with those in Wei (2007) and Ho (2006), which also explored the effectiveness of the process approach by comparing with the traditional product approach. In their study, students’ attitudes of writing generally improved after being taught by writing in the process approach in the experimental research.

The main focus of this study was to explore students’ attitudes to the product approach in EFL writing classroom. Qualitative data raised an interesting question that even though the product approach contained more disadvantages than the process approach (Prosser & Webb, 1994), a considerable number of participants (32.67%), however, still preferred the product approach considered their experiences in early schooling. In this study, interviewees of choosing agree and strongly agree demonstrated that if L2 writers were responsible for their writing and to provide readers useful information, those L2 writers were more likely to devote more and write better. For example, if the essay that an engineering student produced was used for solving an engineering problem, this student might think about whether readers were able to understand the principles elaborated in his/her essay and the writer might discuss with readers for constructive suggestions to improve the quality of the essay by editing repetitively. Only in this case students showed great interest in the product writing activities and had an enjoyable writing experience. This finding was similar with Zamel’s research (1983), in which the motivation to language learning could be stimulated and promoted when the language is used purposely and communicatively.

Another reason for students’ preference of applying the product approach was using the model text, a tool for inspiration was also mentioned in this study. Traditionally the model text had been assumed as a technique to help students learn to write, whether in their first language or other foreign languages, by imitating the styles of those regarded as successful writers. However, using samples for imitating had also criticized, for it was generally seen as “stultifying and inhibiting writers rather empowering them or liberating them” (Eschholz, 1980, p.24). But it was worth noticing that some respondents raised a question that how to adopt samples in the feedback. The exposure to model texts in the feedback enabled students to observe their writing problem in lexicon, form, discourse and content by comparing the draft written by themselves and the text written by other authors. This finding echoed Saeidi and Sahebkheir’s (2011) experimental study on applying model essays to EFL learners: model essays significantly affected the accuracy and complexity of English learners writing performance. Numerous researchers tended to agree that model essays as feedback played a significant role in improving writing quality and writing performance (Saeidi & Sahebkheir’s, 2011; Watson, 1982).

5.2 Interpretations of the process approach

Part B of the questionnaire presented the writing activities in each writing stage which have won student participants’ preference. This study found most of the participants held the view that the prewriting activities were essential, like preparing a writing timetable and organization, consulting references, and discussing writing processes with supervisors and peers. For example, the statement Item Pre1 ‘I make a timetable for the writing process no matter it is requested by my supervisor’ and Item Pre6 ‘I consult references for more information about my topic’ were largely endorsed, however, Item Pre3 ‘I write without a written plan’ has received substantial disagreement. Based on Mahnam & Nejadansari (2012), there were significant differences in experimental and controlled groups which performed and did not perform prewriting activities separately. The participants in Mahnam & Nejadansari’s study were 23 adult EFL students with advanced English writing proficiency and have written 5 argumentative essays, while the participants in the present study were postgraduate international students who got a score of at least 6.5 in IELTS writing and studying in the UK, which means the English proficiency of the participants in this study was similar with that of those EFL students in Mahnam & Nejadansari’s study.

Richard and Rodgers (2001) had stated the drafting stage was the most significant phase in the whole writing journey because drafting existed everywhere. For example, Item D5 (I discuss various points of view in my writing) might suggest the importance of arguments and counterarguments to develop the quality of academic essays. This finding is in line with Nussbaum and Schraw’s study (2007) that a better argument and counterargument composes of stronger rebuttals and more balanced reasons, which enables students to win an effective argumentation form in essays with the integration of arguments and counterarguments.

It had been argued that teacher feedback was an indispensable resource in the writing process (Diab, 2016; Keh, 1990; Ruegg, 2015; Zhao, 2010). Teacher error correction was one of the most common feedback activities in Chinese English writing classroom (Yang, Badger & Yu, 2006), the result of which was contrary to Zhang’s (1995) that ESL students had a stronger desire for teacher feedback but echoed Diab’s (2016) that ESL students used peer feedback and teacher feedback to improve their writing. All student interviewees stated that they got used to receive feedback from teachers, especially face-to face conferences which could give ESL/EFL writers precise comments and had a beneficial effect on both written and oral work. In these interviews, most of the participants preferred to choose teacher feedback in the revision stage after finishing their first draft. Meanwhile, peer feedback was also criticized by few participants who thought it was not quite effective because peer’s language level simply allowed them to give constructive suggestions on the lexicon levels rather than the deep level of the writing itself like content, form and organisation. This finding was consistent with Ruegg’s (2015) claiming that teacher comment offered an advantage over peer feedback in terms of improving students’ grammatical ability in English writing.

5.3 Interpretations of the interviews

5.3.1 Supportive voices on the process approach – nature of academic writing